|

| An Interconnected Sea of Islands |

|

This year, we aim to present Taitung to readers using a new, geo-thematic approach. We will explore the interplay between Taitung's unique geographical features, environment and climate on the one hand, and the culture, economy and lifestyle of its inhabitants on the other. In doing so, we hope to impress upon readers a deepened appreciation and heightened curiosity for our county. The first four issues of Taitung Times in 2024 explored Taitung's plains, forests, rivers and coastline. This fifth and penultimate issue focuses on Taitung's offshore islands, and we will finish the year with a special edition dedicated to "spatial sacrality" in Taitung.  On a clear day in the coastal areas of Taitung, as you gaze out over the seascape, your eyes are naturally drawn to Green Island (Lüdao), standing resolute and unbudging in the distance, a familiar landmark, yet full of intrigue. Slightly further out and to the south, just beyond the horizon from mainland Taiwan, lie Orchid Island (Lanyu) and the uninhabited peak from the same underwater volcanic range, Little Orchid Island (Xiao Lanyu). While these far-flung islands were often forgotten or neglected, they hold deep significance for local Indigenous populations and are a part of what Austronesian scholar Epeli Hau’ofa called “our sea of islands,” pathways connecting the Austronesians of the South Pacific Islands, from the earliest patterns of migration out of Taiwan to the more recent resurgence in recognition and reconnection of their shared maritime routes, languages, and cultures. This concept aligns with the Austronesian worldview—an island is a vessel, and the ocean is a road—emphasizing that the sea is not a barrier but a connector, linking communities, knowledge, and traditions across vast waters. VOLCANIC GEMS

Taitung's main islands stand as geological marvels, volcanic rock formations thrust from the depths of the Pacific. Green Island cradles one of the world's rarest treasures—the Zhaori Hot Spring is one of only three saltwater hot springs in the world, offering visitors a rare bathing experience with panoramic ocean views. Orchid Island, the larger of these two volcanic formations, rises from the sea with rugged coastal cliffs, sculptured by millennia of wind and waves, standing in stark contrast to the lush, orchid-dotted interior that gives the island its name. Also known to locals as Ponso no Tao, Orchid Island's isolation has preserved not only its natural splendour but also the authenticity of its indigenous inhabitants, the Tao (Yami). UNDERWATER GARDENS

Cradled by the Pacific, Green and Orchid Islands are encircled by vibrant coral reefs, forming rich underwater gardens teeming with diverse marine life. These reefs are not just visually stunning; they are crucial to the islands' thriving ecosystems and the maritime traditions that have persisted for generations. Due to their isolation and the passage of the Kuroshio Current, the islands have developed subspecies or endemic species distinct from those on mainland Taiwan, showcasing remarkable biodiversity. The surrounding coral reefs host a kaleidoscope of colourful fish, and international visitors are further drawn by the chance to encounter majestic whale sharks, migratory species like humpback and sperm whales in winter and sea turtles that frequent the clear waters and often come ashore to nest. This rich marine biodiversity offers a visual spectacle for divers and snorkelers and is a vital component of the region's cultural heritage, however it also creates a tension between environmental balance and carrying capacity for visitors. Green Island and Orchid Island have each developed their own distinct, semi-enclosed ecological and social systems, with their own habits and unwritten norms aligned with natural seasons and the rhythms of daily life. ISLAND HORIZONS

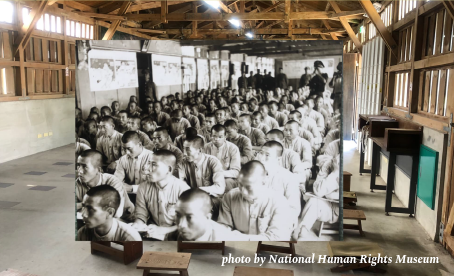

The marginality of these remote islands and their people led to a human development and worldview distinct from mainland Taiwan. For much of the 20th Century the remote islands were beyond the horizons of ordinary Taiwanese and associated with exile or waste. During the White Terror period and until the end of Martial Law in 1987, Green Island was home to political prisoners, where they could be kept out of sight and out of mind. Some former prisoners became critical figures in Taiwan’s democracy movement and one can now visit the Green Island White Terror Memorial Park, which was transformed from prison into a museum and tourist attraction in 2002. Orchid Island, about 40 miles from mainland Taiwan, also had a conflicted history. Its remoteness shielded the Tao from global forces and has helped to preserve their culture. Under Japanese rule, outside development was forbidden, as the island was designated as a fieldwork site for anthropological study, with the Tao people as subjects for research. Later, in 1982, Orchid Island became the dumping ground for Taiwan’s nuclear waste, when the government secretly, and without seeking the consent of locals, constructed a huge storage facility, which now holds over 100,000 barrels of nuclear waste. To this day, the lingering issue of nuclear waste remains largely unresolved.  In recent years, however, a sustainable island philosophy has emerged in response to global emphasis on ecological balance. To address the challenge of transporting waste back to Taiwan, a reusable cup policy was implemented on the offshore islands, while Orchid Island has enforced a nearshore fishing ban to preserve fisheries and ecological resources. The islands now welcome visitors from April to October each year, though summer typhoons that they are usually the first to encounter often necessitate evacuations. From late October to March, residents endure relentless wind and cold rains, and focus on maintenance, preparation and recuperation. The Tao’s way of adapting to nature and embracing the rhythms of island life forms the foundation of a sustainable island philosophy and is key to the reversal of these islands’ status and image, from marginal, to central in the revival of Austronesian cultural identity. GUARDIANS OF MARITIME TRADITIONS

Orchid Island is home to one of the most well-preserved indigenous cultural groups in Taiwan, legendary kayak-builders and fishermen, the Tao people. With such an abundance of marine life it is only natural that their culture revolves heavily around fishing and boat-building and the Tao people stand out as guardians of Austronesian maritime traditions in Taiwan. Their deep connection to the sea is reflected in every aspect of their culture, from their legends and taboos, to the rituals during the flying fish festival season from late March to August, including the flying fish-summoning, preservation and final consumption ceremonies. The Tao put great emphasis on the ritual building of their iconic red, white and black kayaks, the smaller tatala and the larger chinurikuran, using planks attached with dowels and rattan rather than nails, but still robust enough to withstand the unforgiving oceans. At the peak of the flying fish season around May and June, they take their kayaks out at night to catch the flying fish, which torpedo blindly into their nets above the water. Replicas of the iconic boats can also be found at hotels in Taitung City and an artwork replica in Taitung Seaside Park, The Vanishing Boat and Landscape, was created by 200 students and teachers using traditional boat-crafting methods. The boat faces out towards the South Pacific Islands, as the Austronesian ancestors did millennia prior. The fishing industry on Green Island dates back to the Japanese colonial period, and the fishermen developed and preserved their own sustainable form of fishing—bonito pole fishing—which makes for a spectacular display as groups of highly skilled marksmen spear their poles from the boat, unlike in other parts of Taiwan or the world, where fishing nets are used to indiscriminately catch various types of fish, leading to the massive depletion of fish that the world faces today. THE SEA IS A ROAD

More recent journeys of traditional Tao kayaks to the Batanes Islands in the Philippines represent a living history of Austronesian cultural exchange, with related boat craftmanship and navigation techniques found on other Pacific Islands. The Austronesian peoples and language family span the Pacific and beyond, extending as far west as Madagascar, south to New Zealand, and east to Easter Island. There is now some consensus among anthropologists and linguistic researchers that Taiwan, at the Northern edge of the Austronesian sphere, is the original melting pot in which Austronesian languages, culture and music developed, before spreading throughout the South Pacific—a theory known as the “Out of Taiwan” or “Austronesian Expansion”. The Tao share close linguistic and cultural similarities with the Ivatan population of the Batanes Islands in the Philippines. However, later genetic studies indicated they are ethnically closer to the Indigenous of Taiwan Island, notably the Paiwan. This indicates that the cultural and linguistic connections with the Ivatan, were likely a result of trade and maritime routes and shows the complex, overlapping and continued interplay of the Austronesians over centuries. While for some the coast is a boundary, isolating nations and peoples, for the Austronesians it’s always connected them, creating pathways for economic and cultural exchanges that continue today. The emphasis placed on the oceans in Austronesian boat-building, crafts, songs, legends, customs, taboos and rituals underscore their shared heritage, with each island contributing its unique culture and way of life to this interconnected sea of islands. AUSTRONESIAN CULTURAL CAPITAL

Taitung has the highest percentage of Austronesians in Taiwan, with 80 000 people and 7 ethnic groups distributed across the county. They have experienced a cultural revival in recent years and Magistrate April Yao is leading the push to make Taitung the “Austronesian Cultural Capital”. This initiative aims to celebrate and promote Austronesian culture, not just as a historical curiosity, but as a living, evolving tradition. There has been a revival of Austronesian boat building traditions, such as the self-built boats in Changbin and the restoration and teaching of almost extinct Amis and Beinan outrigger canoe craftsmanship. In 2023, the Austronesian Taitung Team participated in the 50th Queen Liliʻuokalani Canoe Race in Hawaii that gathered 2500 paddlers, showcasing Taiwan as the "Mother Island," and just this March, the Flowing Lake Cup Sailing and Austronesian Outrigger Canoe Competition was held in Taitung City. In June 2024, Taitung was the special guest at the 13th Festival of Pacific Arts and Culture held in Hawaii, which featured a “Taitung Week” in Honolulu, showcasing Taitung’s Austronesian song and dance, craftsmanship and arts on the world stage and strengthening its claim as the Austronesian Cultural Capital. Moving on into the future, Taitung will continue to nurture this undertaking and breathe new life into the sea of interconnected islands, with its own islands acting as the vessels on which Taiwan’s Indigenous people will sail out onto the world stage. From the Taitung coast to the offshore islands, celestial navigation, sea rituals, swimming and fishing taboos and departure prayers show a profound respect and deep reverence for nature which has led to the creation of sacred spaces of worship across the county, spaces of enlightenment and renewal, for rituals for birth, death and coming-of-age. We will explore them in the last of our 2024 Taitung Times series — Sacred Spaces. |

| © TAITUNG COUNTY GOVERNMENT 2024 |